They’re going the distance: for MIT’s competitive programmers, North America is just the beginning.

From left to right, Ziqian Zhong, MingYang Deng, and Anton Trygub work on their coding solutions. Photo credit: Michael Roytek for ICPC North America.

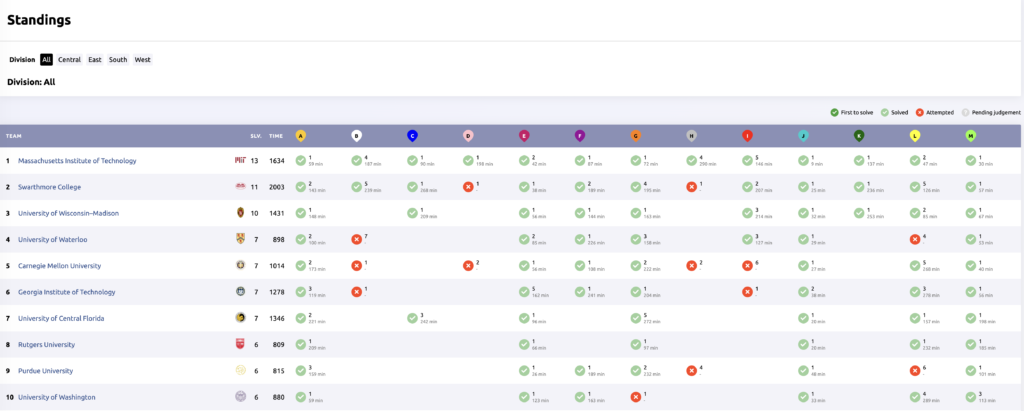

From left to right, Ziqian Zhong, MingYang Deng, and Anton Trygub work on their coding solutions. Photo credit: Michael Roytek for ICPC North America. When you think of computer programmers, you might picture a lone coder, sitting in a cubicle, bathed in flickering light. But you should picture a team: in MIT’s case, a joyous, triumphant team of competitive programmers, bent on solving incredibly thorny problems faster and more accurately than their competition. With a #1 placement in the North American Championships of the International Collegiate Programming Contest (ICPC), MIT’s programming team is now eligible to attend the 46th Annual ICPC World Finals next year. This year, the world finals are being held in Bangladesh; next year’s finals will be held in Egypt.

We sat down with three of the team’s members, Ziqian Zhong (Computer Science and Engineering ’24), MingYang Deng (Computer Science and Engineering ’24), and Anton Trygub (Mathematics and Computer Science and Engineering ’23), to learn what it’s like to compete at the very top tiers of computing.

Many of our readers might have never seen a programming contest before. Tell us a little about the basic rules: what kinds of problems you are faced with, how much time you have to prepare or solve them, and the tools you’re allowed to use!

Ziqian Zhong: We’re typically faced with 10 to 15 problems and five hours. You can code with Java, Kotlin, Python and C/C++. Most teams, including us, prefer to use C++, since it is very concise and usually runs faster.

MingYang Deng: In ACM-ICPC contests, a team consists of three members while only one computer is available, so on average, a member has only a third of the access to the computer. Besides, problems in a programming contest usually require implementing efficient algorithms and data structures, so we typically spend much of our time thinking about solutions before coding.

Do you typically know anything about your competitors, or have friends on opposing teams? Is there trash talking in programming competitions? In other words, what’s the social atmosphere like?

Ziqian Zhong: I personally knew some of my competitors before, and the overall social atmosphere is pretty chill and friendly. We played poker and all kinds of other card games together; I ended up learning two new card games! I guess trash talking is not so popular here.

MingYang Deng: I agree. I made friends with many of my competitors, who are all very nice. People here share the same interests and similar backgrounds. It feels like a community. So there’s no need to be competitive outside the contest.

Anton Trygub: Competitive Programming is different from other competitive activities in the sense that you don’t compete directly against someone, as in football, chess, etc. You just need to do as well as you can yourself, so there is no tension between teams. And on the higher level, competitors know each other, as we participate in the same competitions on a regular basis. We are here to make friends and to help the ICPC community develop!

What makes a problem particularly hard to solve, and which problem was the most difficult in the North American Championships, from your perspective?

Ziqian Zhong: To solve a question, we think and code. Some problems are hard to code, with lots of messy details and casework that is hard to get right. For some other problems it’s hard to figure out the correct solution. Personally, I hate the former kinds of problems (it’s not a typing contest!) and the latter kinds of problems are more popular. Problem H was probably the hardest one and we were the only team that solved it.

Anton Trygub: The problem may be difficult because of different reasons: it might be just heavy implementation with small to no thinking, or requiring some knowledge without which you might just give up, or have a lot of messy details. I prefer problems in which the difficulty lies in the thinking part, in something creative. It’s great to read the problem statement and feel “How can this even be solvable?”

Tell me about a solution you felt was particularly creative, or that you were really proud of!

MingYang Deng: I think Anton’s solution to Problem H and Ziqian’s solution to Problem D are pretty creative.

Anton Trygub: I don’t think that any of my solutions were particularly creative, but Problem H was quite interesting to solve. The setup is, again, “How can this even be solvable”, and then you start looking at some cases and notice some observations, which suddenly add up to the full solution.

Ziqian Zhong: I don’t remember the details about Problem D but I remember it’s a pretty straightforward problem and requires some counting tricks!

How will you be preparing for the world finals next year—what’s involved in that?

Ziqian Zhong: I guess we’ll just do more training contests together. There is no secret ingredient. Mainly just practice more.

MingYang Deng: We will practice more, during which we will refine our strategies.

Anton Trygub: We will have to listen more to our coach on that one 😛 But yeah, mostly practice.

Over the last few years, teams from China, Russia, and Poland have been particularly dominant in the world finals. Why is that, from your perspective—do different countries have different styles of preparation or competition?

Ziqian Zhong: I think many teams in Russia and Poland practiced really hard and they have good strategies. I heard that the Red Panda Team from Moscow State University likes to start with the hard problems and leave some easy problems to the final hour. This is not optimal penalty-wise (the longer you take to solve every problem in total, the larger the penalty) but it probably utilizes the last hour better (the last hour is usually really stressful and it’s hard to get things right). This is pretty different from what we usually pursue.

Anton Trygub: I don’t really think that we should talk about some kind of a trend here, the participants from those countries just happened to be really strong and went to the world finals several times. I hope we can bring a little bit of North America dominance to the finals!

Tell me a little about what competitions like this one have taught you, as a programmer.

Ziqian Zhong: I think it helps me to code faster and more accurately. In a contest, you don’t have much time to debug once things go south.

Anton Trygub: It helps me to go for the most efficient way to implement something, while keeping it clean, as otherwise I would die debugging.

MingYang Deng: It also improves my collaboration skills. In contests like this, you must communicate with your teammates, express your thoughts clearly, work as a team, and believe in each other.

Media Inquiries

Journalists seeking information about EECS, or interviews with EECS faculty members, should email eecs-communications@mit.edu.

Please note: The EECS Communications Office only handles media inquiries related to MIT’s Department of Electrical Engineering & Computer Science. Please visit other school, department, laboratory, or center websites to locate their dedicated media-relations teams.