The Thriving Stars of Data-Driven Medical Diagnoses: early-career women share their professional discoveries and personal journeys on the cutting edge of healthcare and medical technology

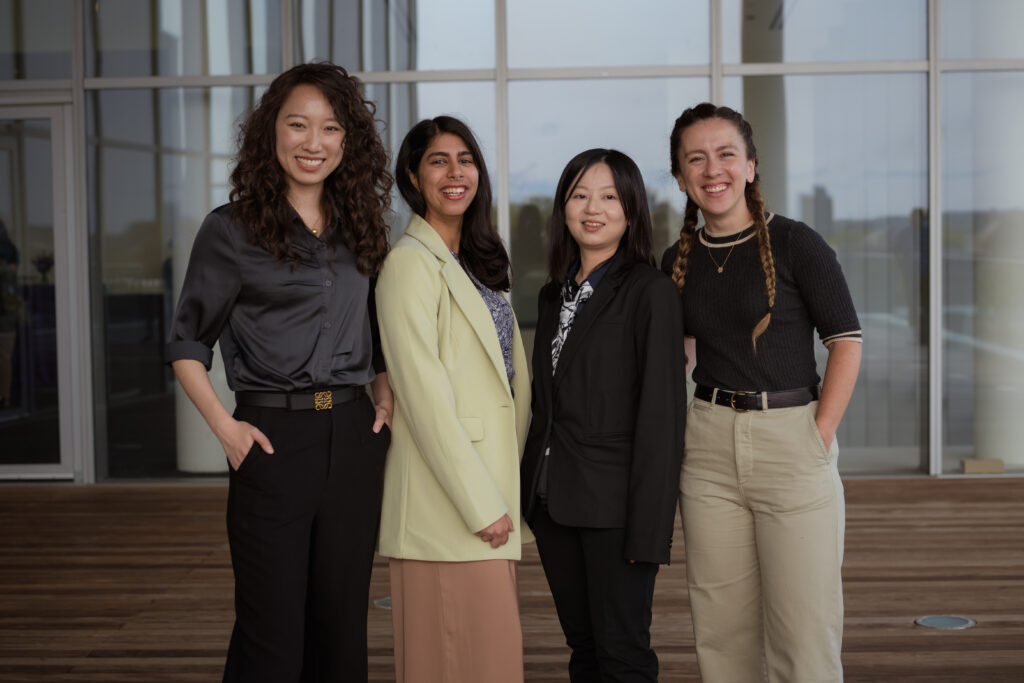

From left to right: Mantian Zue, Geeticka Chauhan, Hsin-Yu (Jane) Lai, and Sirma Orguc. Photo credit: Gretchen Ertl.

From left to right: Mantian Zue, Geeticka Chauhan, Hsin-Yu (Jane) Lai, and Sirma Orguc. Photo credit: Gretchen Ertl. Over the past decade or so, Fitbits and other smartwatches have swelled in popularity, enabling people to track their heart rates, sleep patterns, oxygen levels, and more. This massive amount of data has provided a glimpse into people’s health, sometimes prompting those with poorer stats to make lifestyle changes. Now, researchers are developing more advanced health monitoring and diagnostic technologies to capitalize on the diagnostic power of data.

On May 8, the MIT EECS Department held a research summit on healthcare and medical technology that showcased a few of these researchers’ work. The summit featured four early-career researchers who are developing new tools and hardware for early disease detection and treatment: Geeticka Chauhan, Hsin-Yu (Jane) Lai, Sirma Orguc, and Mantian Xue. Each speaker gave a short talk about her research and shared her career journey thus far. Afterwards, the speakers convened on a panel, moderated by Professor Carol Espy-Wilson of the University of Maryland at College Park.

Lai, Orguc, and Xue, all MIT PhD graduates, each shared their research on developing technology for real-time health monitoring. During her PhD, Lai developed health monitoring software to help with early diagnosis of Alzheimer’s and other neurodegenerative diseases. The software works on smartphones, iPads, and other mobile devices, making it easy for anyone to use. “I really want my tech to be accessible,” she said.

To make diagnoses, Lai’s software tracks people’s eye movements and then uses math and machine learning to determine if there’s a lurking neurodegenerative disease. Essentially, it “mimics what’s done in the clinic on a mobile device,” she said. In this way, people can easily monitor themselves for neurodegenerative diseases on-the-go and hopefully catch any diseases as early as possible.

Like Lai, Orguc also developed a real-time monitoring system for neurological diseases during her PhD. But instead of tracking eye movements, her system directly monitors brain activity. To do this, she built a scaled-down version of a wireless device that’s worn on the head. What’s more, this system comes with a science fiction twist – it can also manipulate brain activity in real-time. Because of this, this system could eventually double as a way to treat neurological diseases, such as Parkinson’s or epilepsy.

While Lai and Orguc’s research each target a single biological function, Xue is working to track a diverse array of them. During her PhD, she developed a technology platform that uses hundreds of biosensors to monitor different biological functions, such as sweat and breath composition. With this wealth of health data, doctors can make better-informed diagnoses and quickly adjust care to prevent and treat diseases.

But making an accurate and reliable system with hundreds of biosensors is incredibly hard. Each biosensor behaves slightly differently from the next due to manufacturing variations. To solve this problem, Xue took inspiration from human senses. After all, human senses aren’t perfect, but the brain can still draw reliable conclusions about our environment, she said.

To mimic this system, Xue incorporated machine learning in her platform to act as the brain, taking in error-ridden measurements from the biosensors and then interpreting it to produce accurate and reliable health data. With this solution, Xue believes that continuous healthcare monitoring is “where biosensors will shine.”

Finally, Chauhan, a current MIT PhD student, is approaching health monitoring from a different angle. Instead of real-time monitoring, she’s developing a robust diagnostic tool that leverages the same image data and reports that doctors use. The tool assesses cardiovascular disease in patients by using chest x-rays and radiology reports. At the heart of this tool is artificial intelligence. “There’s a revolution [in healthcare] right now,” Chauhan said. “AI is going to be a real partner to patients and doctors.”

But many doctors are wary of the black box of AI. To help overcome this, Chauhan has designed her tool to show doctors exactly where in the x-ray or report its conclusions come from. By building a transparent tool, she hopes that “we can develop trust between doctors and machines.”

The four speakers also shared their stories behind their research, walking through their journeys starting from childhood. All of them cited doubts in their academic abilities early on, often due to being one of the few – and sometimes only – women in the room. For example, Lai had originally wanted to be a physicist growing up. But when she attended a Math Olympiad in high school with no female peers, she had trouble making friends, and the isolation hurt her ability to solve problems. In turn, she doubted her math skills and instead, pivoted to becoming an electrical engineer. Eventually, she formed a support system of mentors, peers, and family who has helped her move forward in her career. But “what I really struggled with was a lack of role models – someone who you can imagine you can be,” Lai said. Orguc, Xue, and Chauhan also brought up similar struggles with internal doubt and heavily credited their support system in helping them overcome this doubt and succeed in their careers.

Many attendees appreciated hearing the speakers’ stories. “It’s not something you could just Google,” said Mathew Ganatra, an MIT alumnus. One undergraduate woman found the stories “relatable,” especially those about the speakers being encouraged by their families to fall in love with STEM as children and fight their doubts about fitting into a boys’ club. Saba Zerefa, an undergraduate woman interested in pursuing a PhD, liked hearing about the speakers’ extracurricular activities, such as organizing conferences. “I didn’t know what PhD students did other than research,” she said.

This research summit, sponsored by Jane Street Capital, was the second annual summit in a series hosted by the EECS Department’s Thriving Stars initiative. The initiative aims to increase the percentage of women and underrepresented genders in the EECS PhD program. Through this summit, Thriving Stars is furthering its mission by providing a platform for women to share their research and stories with others. “It was great to learn about female work in [my] field,” said Muchao Ye, a male PhD student at Pennsylvania State University who works in healthcare informatics.

Going forward, all four featured speakers will continue to work in healthcare and medical research, although some have pivoted their focus from their PhD work. Lai is currently a postdoctoral researcher at Harvard, developing algorithms for adaptive medical treatments. Orguc has shifted to computational neuroscience research and is currently a Schmidt Science Fellow at MIT. Xue remains in her specialty, working on health sensing technology, but now as a hardware engineer at Apple. Finally, Chauhan is wrapping up her PhD at MIT and plans to work with doctors to incorporate AI in healthcare.

With these researchers hard at work, the next-generation healthcare technology and medical care is on the way.

Media Inquiries

Journalists seeking information about EECS, or interviews with EECS faculty members, should email eecs-communications@mit.edu.

Please note: The EECS Communications Office only handles media inquiries related to MIT’s Department of Electrical Engineering & Computer Science. Please visit other school, department, laboratory, or center websites to locate their dedicated media-relations teams.